Territorio Ancestral Waorani 'Ome', Ecuador

The territory

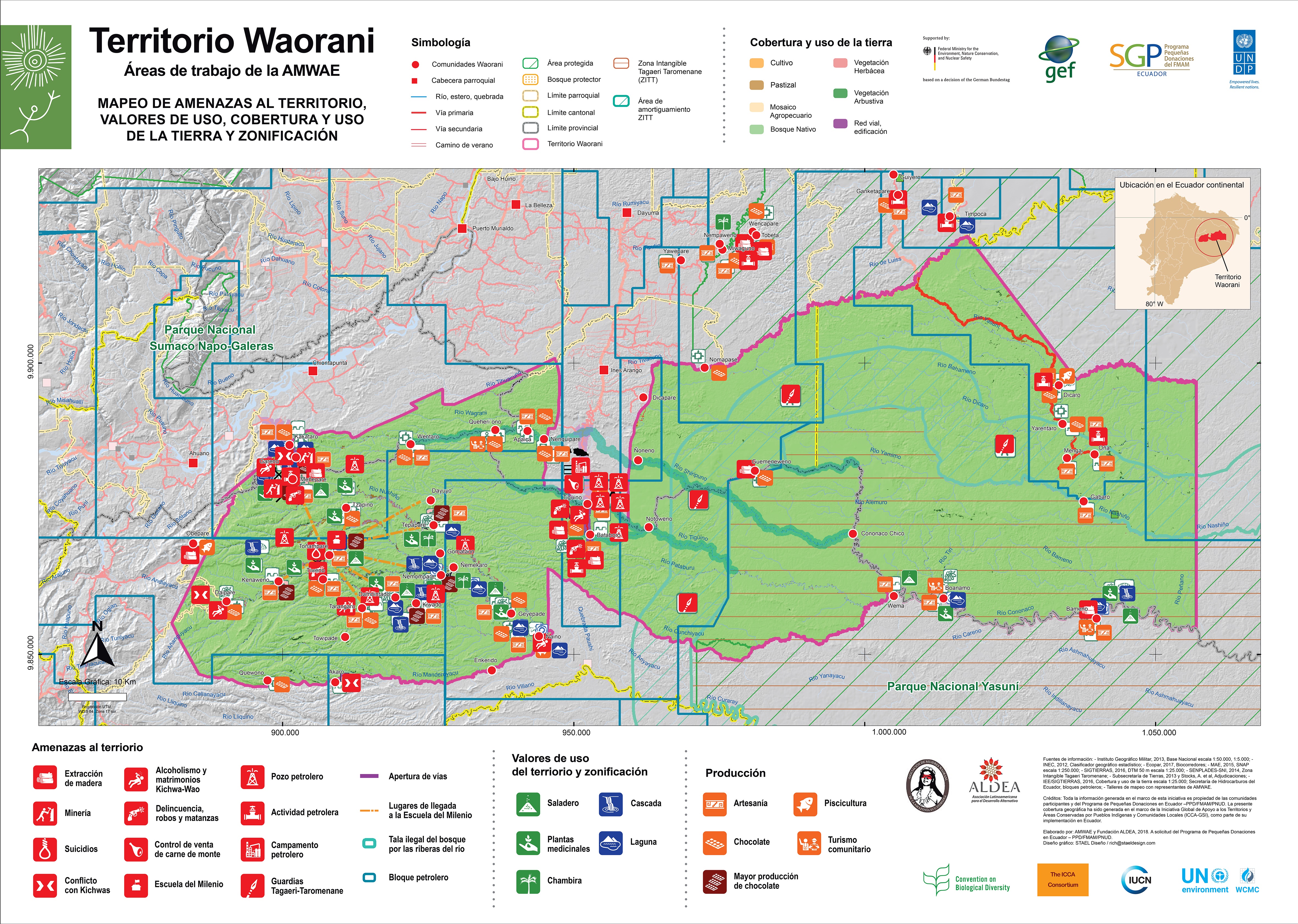

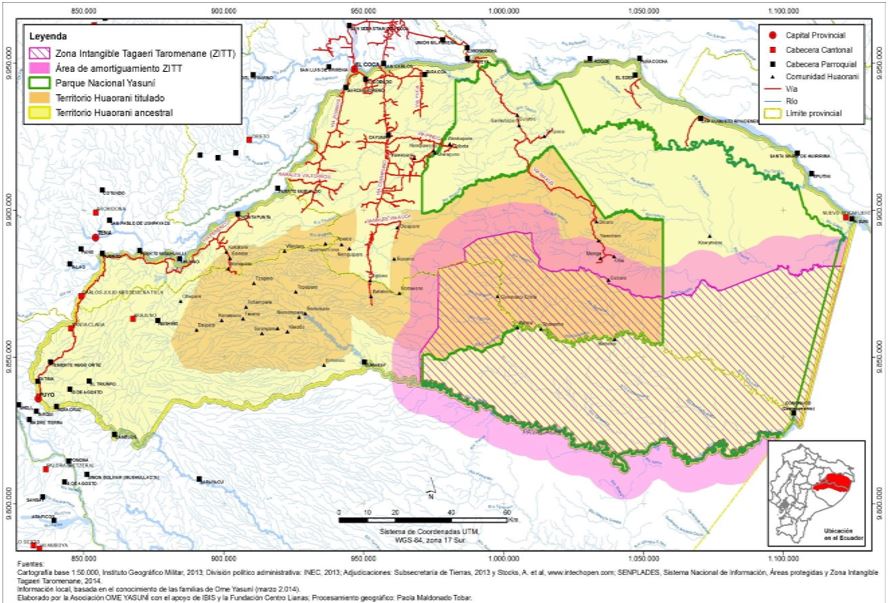

The Waorani territory is located in the eastern part of Ecuador and includes 32 communities within three Amazonian provinces: Orellana, Pastaza and Napo. The Waorani’s ancestral territory covers approximately 2million hectares, and contains several state recognised protected areas such as the Yasuní National Park (which is the core zone of the wider UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve), the Waorani titled territory (see maps) and the Tagaeri-Taromenane Intangible Zone. Although the designations and boundaries of these areas were not defined by the Waorani, they are taken into account hen delimiting their territory and activities.

Map. Zonification in the Yasuní UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve

History

Prior to first contact in the 1960s, the Waorani people lived nomadically in the Ecuadorian and Peruvian Amazon, with no notion of country boundaries. They lived on top of hills and between rivers as hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists. They did not have a strong relationship with the rivers until after first contact, when they transitioned from being a nomadic people organised in family clans to a sedentary people organised in communities that established themselves in riverside villages.

Following the Waorani peoples’ requests for formal recognition, in 1969 the state initially recognised 16,000 hectares as a "Huaorani protectorate" expanding to 612,650 hectares in 1990. Within this framework, the Organisation of the Huaorani Nationality of Ecuador (ONHAE) was created in the 1990s (changed to Nacionalidad Waorani del Ecuador, or NAWE, in 2007). Today, 679,220 hectares are recognised by the Ecuadorian state as belonging to the Waorani and are known as the Waorani titled territory (Territorio Huaorani titulado).

In 2005 the Waorani women organised themselves into the Association of Waorani Women of the Ecuadorian Amazon (AMWAE). This organisation has played an important role in the preservation of their customs, ancestral knowledge, the defence of the territory, and the development of productive activities. While the AMWAE does not have a specific territory, its spatially determined by the membership of the Waorani women, and by the impact of the activities and projects that they carry out. Some of these activities include territorial governance, conservation of the territory and addressing threats.

Biodiversity

More than 98% of the Waorani territory comprises tropical forest, with unique and taxonomically diverse fauna and flora. The Yasuní National Park has a close relationship with the Waorani territory, protecting diverse forests, rivers, estuaries, and complex lake systems.

The region is home to more than 2,000 species of trees and shrubs, 204 species of mammals, 610 species of birds, 121 species of reptiles, 150 species of amphibians and more than 250 species of fish. In one hectare of the park, 650 tree species were reported, more than those found in all of North America. Some of these tree species can reach 50 metres in height, with trunks of more than 1.5 metres in diameter.

Fauna include 12 species of monkeys—such as the spider monkey, chorongo, chichicos bebeleche, howler and pocket monkey — as well as jaguars, capybaras, pumas, tapirs, anteaters, peccaries, guatines, deer, ocelots and cusumbos. There are also a wide variety of birds, including macaws, toucans, kites, woodpeckers, woodcreepers, sigchas, and several species of hummingbirds.

Threats

The Waorani have experienced huge pressures from oil extraction, logging, indiscriminate hunting for the sale of bushmeat and the urbanisation of certain areas of the territory. This has led to the contamination of their lands and rivers and has caused profound changes to their way of life in relation to the forest. There are significant differences between the different communities involved in the management of the territory. These differences and internal divisions are resulting in infringements of community rules, especially when linked to illegal hunting or logging. Illegal hunting has unfortunately caused the localised extinction of black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) and marimonda populations. Populations of pacas, peccaries and other mammals that play an important role in tropical seed dispersal were also decimated, leading to subtle changes in forest composition.

Diversifying Livelihoods

The Waorani people have ancient culture, traditions and knowledge that are still very present. Many of the Waorani people maintain a subsistence economy based on sustainable crop growth, hunting, fishing and fruit gathering. For AMWAE, a significant focus is the conservation of their ancestral knowledge and language, including knowledge of handicraft production and medicinal plants. There is a long-standing relationship and a strong sense of responsibility for the ancestral territory, with the aim to ‘conserve in order to produce, and to produce in order to conserve’.

The women of AMWAE have played a leading role in developing self-strengthening enterprises. These are aimed at addressing the needs of the community, conserving their territory for their material, immaterial, cultural and spiritual wellbeing. These activities seek to reduce pressure on the forests in order to maintain them for future generations.

These activities include:

- Cultivation of certified cocoa for chocolate production.

- Planting in nurseries.

- Chambira (a spiny palm native to the Amazon) cultivation for the production of handicrafts such as bracelets, necklaces, earrings, bags, hammocks, bread baskets, traditional costumes, etc.

- Collection of dyes and seeds from the forest to make handicrafts.

- Sale of tree seedlings for reforestation

Products are sold nationally and internationally at fairs, as well as in shops across the country's cities, such as Puyo and Coca. They also promote community tourism as a way to raise awareness of their territory. AMWAE's actions to restrict the bushmeat trade has had a significant positive environmental impact in one of the world's most biologically diverse areas. The restriction of bushmeat trade has allowed animal populations to recover and is especially important for the long-term viability of vulnerable and endangered species.

Management and Governance

Governance arrangements of the ICCA are complex due to overlapping authorities of the Association of the Waorani Nationality of Ecuador (NAWE), state authorities, and other stakeholders operating within the region.

At the community level, the Waorani organise themselves through communal assemblies. The leadership of the elders (Pikenanes) is fundamental in these assemblies. The Pikenane are made up mostly of well-respected men, but do also contain women. In the communal space, women traditionally have an important decision-making role, further strengthened through their productive activities. The various Pikenanes have quite different views of how to manage the territory: some are in favour of extractive activities, while others oppose them.

The legally recognised territory of the Waorani (Territorio Huaorani titulado) is governed by NAWE, which is considered the highest Waorani territorial authority. Although women are excluded from this particular political structure, the AMWAE is actually seen as part of NAWE. Through NAWE, AMWAE is part of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) and the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE). While NAWE is responsible for dialogue with external actors, AMWAE has its own role (and voice) in global, Ecuadorian and Waorani societies.

The women of each community, and those who are part of AMWAE have key roles to play in community cohesion. Women have greater ecological dependence, and less access to oil or administrative salaries, and their opposition to extractive activities is generally much greater.

Governance is therefore weak but it is improving and can be further strengthened if AMWAE's capacity for “self-strengthening” processes is considered. The classification of AMWAE's territory lies between a (1)‘defined’ ICCA and a (3)‘desired’ ICCA (see the different statuses of ICCA here). It is closer to “defined” when thinking about their deep connection with the Waorani territory and the demonstrated positive conservation outcomes of their activities. But it is closer to (2) “disrupted” when accounting for the challenging governance arrangements that result from complex relationships and territorial delineation.

This case study was originally published by UNEP-WCMC in March 2021. The content was provided by the custodians of this ICCA. The ICCA has been self-declared and has been through a peer-review process to verify its status. More details on this process can be found here. The contents of this website do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UN Environment Programme or WCMC.

This case study was facilitated by the Small Grants Program in Ecuador (PPD/GEF/UNDP – GSI ICCA), in collaboration with the Latin American Association for Alternative Development (ALDEA).

The photographs in this case study are from the Small Grants Program in Ecuador, the collaboration agreement signed with ALDEA indicated that the production, audiovisual, photographic material or generation of documents within the framework of the GSI-ICCA/PPD project are from the PPD.