Kawawana , Senegal

Association Kawawana

Kawawana derives from the Djola expression "Kapooye Wafolal Wata Nanang" meaning "Our patrimony, for us all to preserve". Created by fishermen in 2008, the association APCRM (Association of Fishermen of the Rural Community Mangagoulack) includes nowadays members of the communities of eight villages of central Casamance in Senegal. The original purpose of the APCRM was to halt the decline in the number, quality and diversity of local fish stocks. A conservation area was demarcated and rules have been put in place to fight against free access to coastal waters, against the use of destructive methods, against the resulting high pressure on the stocks of local fisheries resources. APCRM has established an Indigenous and Community Conserved Area (ICCA) named Kawawana with a no-take zones and other areas of limited fishing to protect local fish stocks. Due to a lot of determination and diplomacy, APCRM obtained the statutory rights of management of the coastal zone for Kawawana in 2010, including a preferential right to fish on the local coastal strip. In Senegal, Mangagoulack is the first local community to have received such devolution of management rights of coastal fisheries.

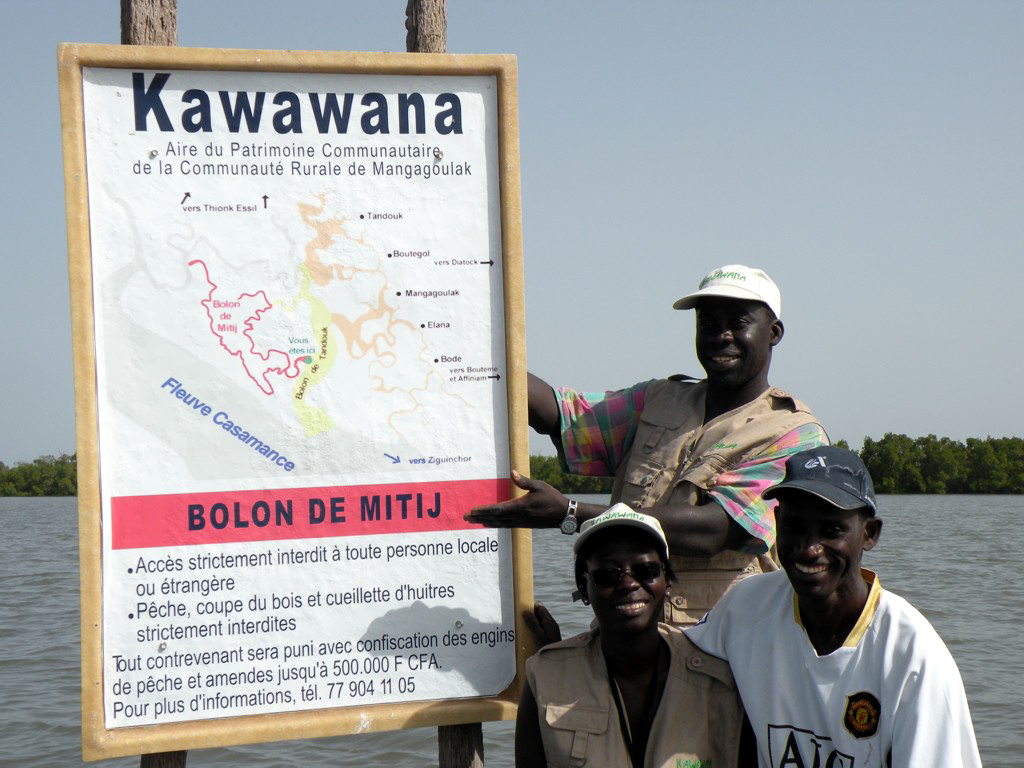

Today, three zones are established. These three zones are marked by colors (red, orange and yellow) corresponding to three different types of management. The red zone is a no-take area where no fishing or collecting shells or wood is permitted. The orange area is reserved to fishing for the local market and consumption. The yellow area is open to fishing, but with limitations of allowed fishing methods and gear. The color-code and management regime is communicated using large signs located at strategic transit points with communication details such as a phone number, so that “foreign" fishermen can immediately ask for clarification. But these signs are not the only tools to inform users. Indeed, a mixed system combining modern and traditional methods is used, that ensures proper dissemination of rights and prohibitions throughout the zoning system, which even "foreign" fishermen were soon familiar with. Moreover, fetishes are placed at appropriate locations and provide a traditional reading of rules to follow.

The red no-take zone is marked by fetishes that revived the tradition of "sacred bolongs". This area acts as a refuge for aquatic life. Mangroves and inlets provide habitat for humpback dolphins, manatees, fish from the coastal areas and shellfish. The sacred nature prohibits any usage of resource and is engrained in Djola culture in the marine and terrestrial. Indeed, each Djola villages has always had at least one sacred grove, “sacred bolongs" and mangrove existed here and elsewhere before the introduction of laws that allowed free access to coastal areas.

The orange area is reserved for fishing for local consumption and markets. Each village has its “bolong" but local fishermen can fish where they want, provided they follow the local rules and restrictions. The product of their fishing must be disposed of on site because the primary objective of Kawawana is to improve food security of the local community. “Foreign" fishermen cannot access this area, unless they are invited by a resident and housed in the community.

The yellow area is open to everyone with the condition of compliance with restrictions on fishing methods and gear. Outboard engines are prohibited here and types and mesh size of allowed nets are clearly defined. Monofilament nets are prohibited and if any such is found in Kawawana, it will be burned in place.

The return to a more traditional management ended the decline of resources, which was a consequence of the previous open access. Indeed, migrant fishermen with their destructive fishing methods were previously a major cause for the depletion of fish stocks. Obtaining the rights to manage the coastal zone has played an instrumental role as it gave the opportunity to expel migrant fishermen, who do not respect the rules, from Kawawana. It was a great success, creating a new sanctuary for wildlife.

The new management quickly had an impact on fish stocks, with a direct and positive impact on the local diet, as most proteins come from fish in these communities. As the availability and quality of fish has improved, there are more than 10,000 local residents who have a better source of protein for a price that is quite affordable. Only three years after the creation of the Indigenous and Community Conserved Area (ICCA) in Mangagoulack, local fishermen say they have seen an increase of 100% of their catches. This outstanding result is confirmed by the analysis of data from scientific monitoring (monitoring also conducted mostly by fishermen themselves) which showed a doubling of catches over the baseline.

To ensure that the balance is preserved, APCRM actively monitors wildlife and socio-economic assessments are also conducted regularly. Fishermen quickly learned scientific techniques, despite a lack of formal education. Data are captured and analyzed with a small computer using spreadsheets and other software. In addition to their extensive knowledge of the fisheries, they have acquired new skills useful to the environment and society at large.

Beyond improving biological habitats and natural resources, Kawawana facilitated other positive developments in the community. Fuel for the patrol boat is financed by a monthly collective fishing trip. Many volunteers sign up as crew for patrols, despite not being paid. Collaboration and solidarity within the community are greater than ever. Collaboration spurs alternative projects; the association is trying to strengthen damns that protect areas of rice cultivation for example. These efforts are becoming increasingly important to improve community resilience against the impacts of climate change (including sea level rise). In the long-run, the return of fishing rights to local communities and the effectiveness of the new management regime will inspire other communities within Senegal and beyond. Kawawana will certainly have an impact on the ongoing national debate about the future of protected areas in Senegal.

However, the current success was not achieved in a day. Years of hard work, marked by several intermediate stages, contributed to the success of Kawawana. At first, burning monofilament nets and replanting mangroves were trialed and proved insufficient. Subsequently, negotiations with the government to obtain the management rights have been very difficult. However, after lengthy discussions and major lobbying, the Kawawana fishermen finally obtained official documents in June 2010, signed by the Regional Council and the Governor of the Casamance. It is important to emphasize that this initiative was born from the roots and a request for support and advise by NGOs has only been made, once the principles and vision of Kawawana was firmly established. The organization currently operates independently after having had a little help from Cenesta, GEF SGP and the New York Foundation FIBA.

Kawawana was a great success for the community at large. According to local fishermen, the catches have improved since the creation of the APAC fish became more numerous, larger, more healthy. Many said that, "the good life is back." Kawawana activities have recently extended, temporary restrictions of shellfish collection were put in place by local women to allow sufficient time for reproduction and an extension of Kawawana is underway. Kawawana became a source of pride for the local community and its eight villages gladly accept their new role as guardians of nature. The fishermen's Association has improved natural resources qualitatively and quantitatively. There is better food, more income, reduced conflict, improved internal solidarity and a better awareness of the issues, problems and solutions. Kawawana could well set a precedent for how local communities on the coast of West Africa can manage marine resources in a sustainable manner based on both traditional knowledge and organisation as well as modern technologies. Other communities have already requested support from APCRM for the establishment of protected areas in their community in coastal areas, but also in the inland regions.

For more information on Kawawana please see the ICCA Consortium webpage here: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/index.php/2014/12/1...

This case study was originally published by UNEP-WCMC in August 2012. The content was provided by the custodians of this ICCA. The ICCA has been self-declared and has been through a peer-review process to verify its status. More details on this process can be found here. The contents of this website do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UN Environment Programme or WCMC.

.jpg)